Drs. Shaf Keshavjee and Marcelo Cypel with the Ex Vivo System, their transplant-altering invention. Photo by Tim Fraser.

How UHN’s doctors invented a revolutionary way to repair and transplant damaged donor organs.

By Brian Borzykowski

Picture this: inside Toronto General Hospital is an operating room that looks just like any other, except no patient will ever be wheeled into it for surgery. The space is filled with organs –livers, lungs, hearts, kidneys, pancreases – living in a plethora of strange-looking devices, which repair and regenerate these body parts so they can be used for transplants. Surgeons might walk into the room, grab an organ and walk out the same way they’d choose other surgical instruments or supplies.

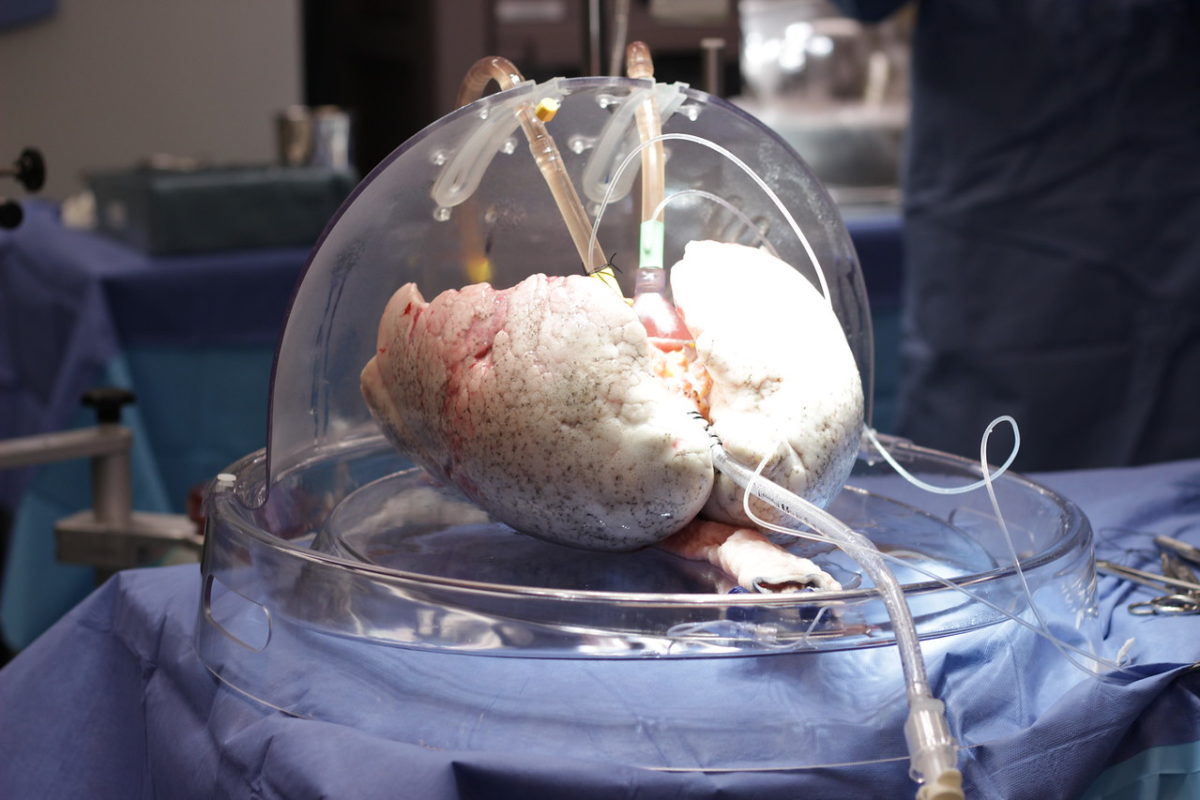

While the room doesn’t yet exist, there is a smaller version in OR 11 at Toronto General Hospital, where lungs are kept alive and breathing, and are treated ex vivo –outside one’s body – before being transplanted into a patient. The key piece of equipment in this OR is a dome-like device where damaged donor lungs, ones that would be unsuitable for transplantation under normal circumstances, get treated, fixed and made usable again. While a lot of medical devices are heralded as breakthrough technologies, the Toronto Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion System, as it’s called, really can make a difference as to whether someone lives or dies.

Centuries of innovation

The quest to build an Ex Vivo-like machine has been going on for hundreds of years– in the 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci made drawings of organs living on external support systems. In the 1930s, aviator Charles Lindbergh and surgeon Alexis Carrel tried to create a perfusion pump, a device that would keep organs functioning outside the body. But it was a team of Toronto General doctors who finally did what many thought was impossible.

In 2008, Dr. Shaf Keshavjee, now Surgeon-in-Chief of the Sprott Department of Surgery, and Dr. Marcelo Cypel, now Surgical Director of the Soham & Shaila Ajmera Family Transplant Centre at University Health Network (UHN) and head of transplant surgery within the Sprott Department of Surgery, built a device and developed a method that could keep lungs alive for up to 24 hours after they had been removed from a donor’s body without needing any blood to run through the organ.

Dr. Keshavjee, who is also the James Wallace McCutcheon Chair in Surgery, Director of the Toronto Lung Transplant Program and Director of the Latner Thoracic Surgery Research Laboratories, had originally been trying to find a way to use gene therapy to modify donor lungs and make them more likely to be accepted by a transplant recipient.For this kind of gene therapy to work, he had to develop a way to treat donor lungs outside the body rather than in a patient. If lungs could be kept alive and healthy outside the body prior to transplantation, surgeons could apply different therapies to help heal and repair the lungs and make them almost as good as new.“We want to get to the point where we can make an organ that lasts forever,” says Dr. Keshavjee.

The Ex Vivo System allows lungs to live and literally breathe outside a body for up to 24 hours.

The Ex Vivo System allows lungs to live and literally breathe outside a body for up to 24 hours.

Finding the right combinations

It took this long for someone to create a working Ex Vivo System because the stakes are so high– the primary goal for the device is to support the organ. Lungs are extremely fragile, says Dr. Keshavjee, which is why the world’s first-ever successful lung transplant was only done in 1983 – at Toronto General–many years after the first heart, liver and kidney transplants. Until the Ex Vivo System was developed, it was far more difficult to find suitable donor lungs to save a person’s life.

To create this device, Drs. Keshavjee and Cypel had to find a way to perfuse lungs with something other than blood. (Perfusion refers to the way fluid moves through a circulatory system of an organ or tissue.) The problem with blood is that when artificially pumped through the lungs, it can cause inflammation and injury, explains Dr. Cypel, who is also Surgical Director of the Extracorporeal Lung Support Program at UHN.

They had to find a way to keep lungs at body temperature, which is not the norm. When organs are removed from a donor, they typically go onto ice. “That’s how people still preserve organs – they keep them cold,” explains Dr. Cypel. “But you can’t give any treatment to the organ when it’s cold, as there’s not enough metabolism.”

Other steps had to be taken too, such as determining the right amount of oxygen and nutrients to pump into the organ, and they had to keep the lungs ventilated. After joining Dr. Keshavjee’s research team in 2005, Dr. Cypel was tasked with trying to find the right combination of fluids and nutrients, among other elements, necessary to keep lungs alive. It only took about a year before they figured it out. “We moved fast,” he says. “A year later, we kept lungs on the system for 12 hours, and it looked perfect at the end. We realized that we had achieved a major milestone.”

Understanding the transplant process

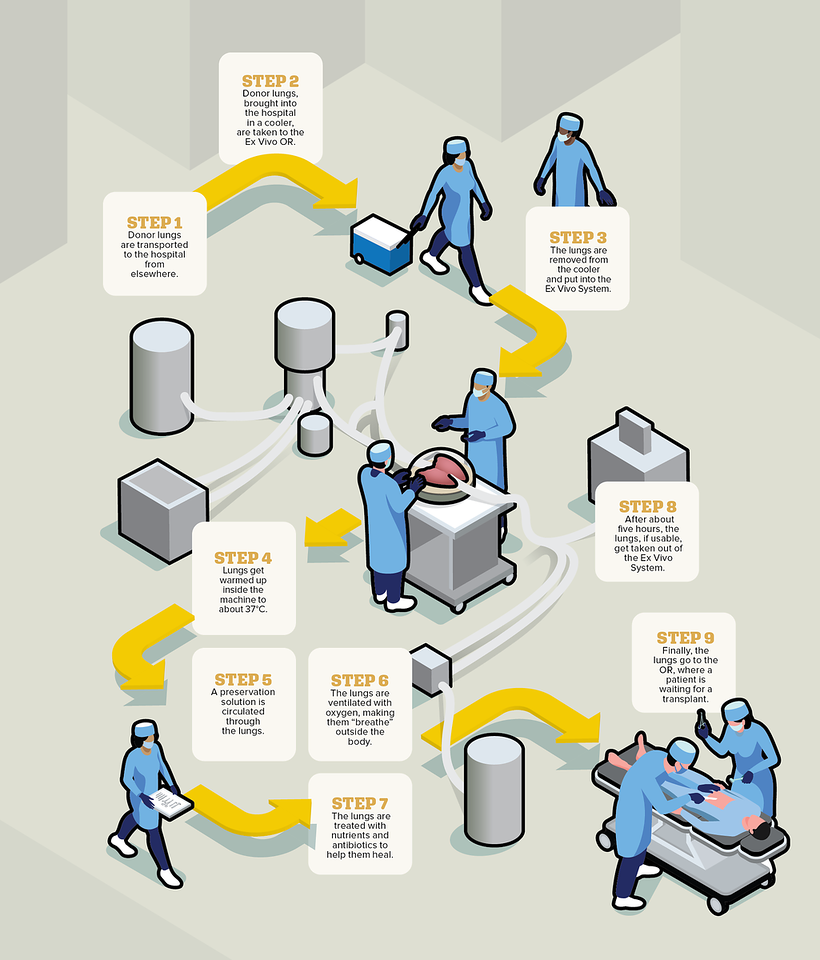

When a donor passes away, their lungs are flushed, cooled, put on ice and brought to Toronto General – as the largest lung transplant centre in the world, lungs arrive from across the continent – where a small team of specially trained organ perfusion specialists put the lungs into the Ex Vivo System’s dome. The dome is connected to a circuit, which consists of tubes, a pump, a ventilator and a filter, through which the liquids, oxygen and nutrients flow. The lungs are then warmed over about 30 minutes, at which point ventilation starts, causing the organ to breathe in and out, like it would inside a body, right there in the dome.

Over the next several hours, doctors essentially operate on the donor organ to try to make it healthy again. They might remove water from the lungs, treat them with high doses of antibiotics, take out blood clots and more. Every hour, the surgeon, such as Dr. Keshavjee, gets updated on how the lungs are doing, and usually about three hours into this process, they will know whether the lungs are usable. While lungs can now live on the Ex Vivo System for up to 24 hours, they are usually kept it in there for about five. Once the process is over, surgeons transplant the donor lungs into the patient, who would have already been waiting in the hospital.

When Drs. Keshavjee and Cypel started telling people they had succeeded in creating the completely donor-funded Ex Vivo System, launched with a generous gift from the Latner family, some were skeptical. “They didn’t believe we did it,” recalls Dr. Keshavjee. Once everyone realized the doctors did indeed accomplish what so many before them couldn’t, they started to clamour for this technology. Today, hospitals around the world use a version of their Ex Vivo System.

At Toronto General, surgeons currently perform double the number of lung transplants they used to, as so many organs that would have been previously deemed unsuitable can now be used. Thousands more people are living healthy and productive lives because of this device. The technology has also been adapted for other organs–Sprott surgeons can now assess and treat livers and kidneys ex vivo and then transplant them into patients – and they are developing similar systems for the heart and pancreas.

In the near future, the organ repair operating rooms, where several systems will be housed to help repair different organs, will be up and running –these ORs are currently under construction. When they’re built, and as the technology continues to advance, many more donor organs will be available for use. Nearly anyone who needs a transplant will get one.

Dr. Keshavjee continues to explore and develop gene therapy. Using the Ex Vivo System, he could make donor lungs closely resemble the recipient, so there’s less risk of organ rejection. One day doctors might remove a person’s own lungs from their body, fix them using the Ex Vivo System and then reinsert them as good as new. “The development of the Toronto Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion System is the biggest advancement since transplantation itself,” says Dr. Keshavjee, who participated in the world’s first successful double-lung transplant in 1986 at Toronto General and has received numerous awards worldwide for this device. “Soon we’ll do this for every organ, and it will save even more lives.”

Ex Vivo needed

85% of lungs that are donated globally are not suitable for transplant. (Source: Lung transplant foundation)

Breathe easy

1,868 Canadians (excluding Quebec) living with a lung transplant in 2018 (Source: Canadian Institute for Health Information)

This article originally appeared in the Sprott Department of Surgery magazine.